Great Moments in Plant Evolution, Part 3: Extinction to Ginkgo

As we continue our journey through geologic time, we will start to see plants that are more familiar to us: plants that reproduce with seeds, such as conifers and ginkgos. In order to understand their origins, we need to briefly visit the Devonian period, when the first seeds appear in the fossil record.

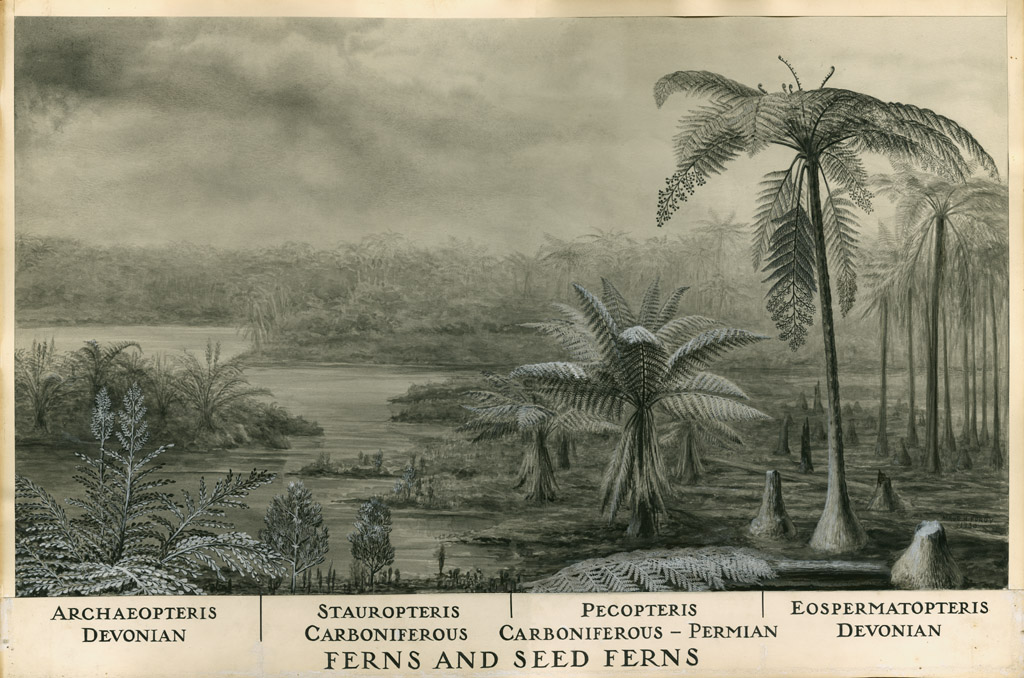

In particular, we find a group of plants that we collectively call seed ferns. As the name suggests, these plants possessed a form reminiscent of ferns, such as frond-like leaves, but these plants reproduced with seeds, which were attached to the underside of those fronds. Some taxa were small and scrambling, while others were treelike forms, but the advent of the seed gave them the ability to survive in new drier ecosystems.

More: Great Moments in Plant Evolution, Part 1: Plants Invade the Land

Great Moments in Plant Evolution, Part 2: The Origin of Trees and Forests

The evolution of the seed meant that plants could reproduce without the significant moisture required by spore-bearing plants. During the Carboniferous, these early seed plants diversified, but were relegated to being understory plants living in drier niches of the steamy, wet Coal Age. During the Late Carboniferous, a global drying pattern began, which gave seed plants an advantage.

It is during this time that we find evidence of the first cycads. These palmlike plants retained that ancient seed fern appearance with frond-like leaves, and flourished during the Mesozoic Era. They have survived to this day, living in tropical climates, appearing somewhat similar to their ancestors. They are prized by plant enthusiasts, but many are threatened with extinction due to habitat loss and poaching. A sad state for a group that has survived for over 300 million years.

With the start of the Permian period, around 300 million years ago, the Earth became progressively drier. The seed plants were well suited to these changes, and spore-bearing plants started to lose their dominance. New plants, such as Glossopteris appeared. These large woody trees had tongue-shaped leaves, which were more similar to angiosperms than the ancient seed ferns. These plants were successful in a variety of habitats and their leaves are found in rocks on many continents, including Antarctica. In fact, Alfred Wegener, who in the early 1900s proposed that continents move over time, used fossils of Glossopteris as evidence to piece together the puzzle that was plate tectonics.

As the Permian neared an end, life experienced the most catastrophic extinction event ever seen on Earth. Over several million years, carbon dioxide levels on the Earth rose, probably caused by massive volcanic activity during this time. The result was extreme global warming that led to the collapse of most global ecosystems, including the oceans. It is estimated that over 80 percent of marine species disappeared, and 70 percent of vertebrate species on land went extinct. Plants tend to be more resistant to extinction events, but the Permian extinction seems to have severely impacted the flora of the time. For this reason, this time is known as the “Great Dying.”

Amazingly, life survived the Permian extinction, and Earth entered the Mesozoic Era: the age of dinosaurs and gymnosperms. Seed plants become the dominant flora, although some spore-bearing plants, such as the true ferns, also diversified, giving rise to many taxa that we know today. Plants like Glossopteris survived the Permian extinction to only disappear in the Triassic, the first period of this time. A group of seed ferns called corystosperms replaced Glossopteris, and became one of the major groups of the Triassic, dominating the landscape with other gymnosperms, such as conifers.

Conifers, our beloved cone-bearing evergreens, appear before the Permian, and go on to flourish in this new Mesozoic world. Throughout this era, they become the dominant flora in a world filled with immense dinosaurs with voracious appetites. The scrappy and quick growth strategy of conifers may have helped them survive the extremes of this new Mesozoic world, and allowed them to survive alongside the angiosperms in the modern world. Today, there are roughly 600 species conifers, but with this low diversity they still dominate many portions of the worlds, including alpine and high-latitude environments.

Even ginkgos, also appearing in the Permian, survive the extinction event, and go on to diversify and flourish during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods of the Mesozoic. Ginkgos were widespread across the world, and even persisted in North America until just 7 million years ago! Today there is one surviving species, Ginkgo biloba, a tree unknown to western science until the late 1600s. This plant has once again become a common tree throughout North America and Europe due to its adaptability to urban landscapes, but is abhorred by some for the wretched smell of its seeds. In my opinion, a small annoyance for a group that has survived so much and for so long.

The history of life on Earth can be unbelievably daunting to comprehend, with so many millions of years before the advent of humans. This is the realm of the paleontologist, searching for clues to understand evolution, and hopefully to shed light on the present. As a multipart series, we will explore some of the major events during the evolution of plants.

Next: Great Moments in Plant Evolution, Part 4: The Dawn of Flowers